On July 22, photographer Angus O’Callaghan’s photographic prints went under the hammer at Leonard Joel. This little known Australian photographer’s works were sold alongside the likes of photographic icons and household names Wolfgang Sievers, Helmut Newton, Max Dupain, David Hockney and Mark Strizic. Ben Albrecht who represents Angus, and is responsible for the rediscovery of Angus’ works, believes the auction was a “really great way of getting his name out there, I really wanted his photography to have a listing on the secondary art market.”

Looking through the viewfinder with Angus it is hard to believe that we are only just now discovering this unique documenter of Melbourne in the sixties. I had the rare and exciting opportunity to sit down and speak with Angus and ask what had inspired his documentation and why had we not had the privilege of seeing it until now. The answer I would find was an inspiring story of never giving up your passion.

Looking through the viewfinder with Angus it is hard to believe that we are only just now discovering this unique documenter of Melbourne in the sixties. I had the rare and exciting opportunity to sit down and speak with Angus and ask what had inspired his documentation and why had we not had the privilege of seeing it until now. The answer I would find was an inspiring story of never giving up your passion.

Angus’ story is not an unfamiliar one for many born of his generation. Born in Melbourne, seven years before the great depression and one of 12 siblings, Angus O’Callaghan began his journey into photography in what most would think to be the last place such a creative endeavor would occur. He was consigned as an unofficial photographer whilst serving for the Australian Army as an engineer in Syria in the Second World War for two years. Here he was responsible with the task of photographing damaged structures and bridges using his own camera, never seeing the photographs beyond the negative stage. He then developed an interest in photojournalism while working as an English teacher in Melbourne. Documenting the Suez Canal crisis of 1956 using a standard 35mm camera, Angus returned with a suitcase full of slides which Women’s Weekly published, his first commercial commission. It was then that he decided to setup a studio as a photographer. “I didn’t actually set up as a fashion photographer or a wedding photographer, I thought, I will do a book that was the thing to do at that time, a book of a city, Melbourne city.”

Japanese camera manufacturer, Yashica, produced the 635 in 1958, a medium format twin lens reflex or TLR camera using 120 roll film at 6” x 6”. It was this camera that Angus captured his social documentation of a changing city, the city of Melbourne.

“I read a lot about professional photographers from overseas, Europe and America and in many ways they were more advanced, except for the few we had here. They recommended the medium format, so I bought two of those at $45 each. They were sitting in a window in Collins Street up near George’s. I remember seeing them in the window there and they attracted my eye and the price, I can buy two instead of one. One for black and white, one for colour.”

Angus would often take a photo of a scene in both mediums. He explains that using these cameras with their fixed lenses was quite a disciplined format to work with and having no telephoto lenses; his principal technique was to walk in close to a subject or walk out. This created a voyeur almost fly on the wall approach to his photographs. “You feel like you could be there.” He says.

The quality of the photographs he found to be better than expected which was confirmed when they were produced in a large format. Angus: “they are quite sharp, more resolution than I expected. Because I was only thinking of publishing my photography at book size, nothing bigger”

His plan was to document his love for the city and publish a book of photographs, to capture an image of a city’s landmarks in a new way. So from 1968 he began documenting the architecture, the people and the city itself, documenting the shifting attitudes and surroundings of Melbourne in the late sixties. Of particular importance for this period of his work is that at the time the city’s Victorian architecture, particularly what was then known as the ‘Golden Mile’ of Collins Street, was being demolished and dramatically redeveloped by Melbourne’s premier demolition fellow ‘Whelan the Wrecker’, responsible for the demolition of many iconic Melbourne architectural sites of the 1960s. Subsequently, the destruction of these buildings prompted the formation of the National Trust of Victoria. Angus remembers seeing Whelan the Wrecker demolishing the city he loved: “He used to drive me mad, walking around the city with all of this destruction going on.” Lucky for us Collins Street is featured quite prominently in Angus’ images, giving us a visual documentation of these absent structures residing now only in our nostalgic, hazy memories.

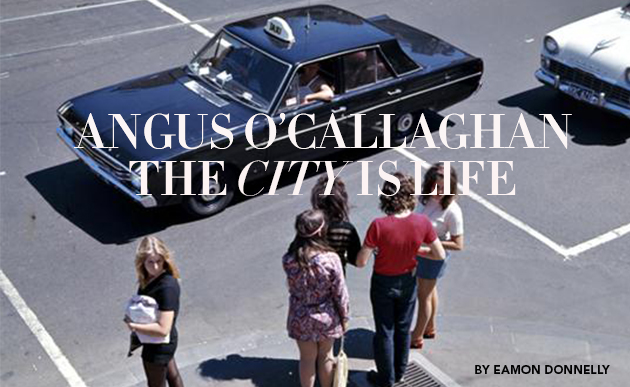

Angus’ images shy away from the stereotypical, almost tourism campaign shots, which were so common in books, published on Australia at the time, ‘Graham Kennedy’s Melbourne’ published in 1967 by Thomas Nelson Limited comes to mind. An agenda to represent Australia to the world in such a way as to project an image of a country full of endless beaches, red earth, bushmen, with modern, livable, thriving cities, whereas Angus captured those elements of a city that weren’t grand. He chose to show a different angle and take an approach that at the time wouldn’t have been marketable to an international audience, something that didn’t reinforce the stereotype of the archetypal Australian image. “You are looking for something that is different and interesting,” He says, “There was a provincialism, ours is the best, if it isn’t, we will make it the best and tell the world it’s the best. So when people saw my work they thought, that’s not really Melbourne, we know its Melbourne, but where’s the grand panorama?”

It is not hard to appreciate that at the time his images didn’t project an image to the world of how we craved to be perceived to an international audience. It’s not until we look at his work 40 years on that the importance of what he captured can finally be recognized and regarded as one of the most significant collections of Melbourne documented on film.

The imagery doesn’t evoke a sense of grandeur, more so the everyday, the commonplace, the changing city. Young & Jackson neon lights, drizzly Melbourne weather on Princess Bridge, new migrant butcher shops spruiking 29 cent Corned Brisket and Lamb’s Fry, Milk bars with ‘Moon Men Fit” broadsheets decorating the pavement, the fondly remembered Southern Cross Hotel with its minty hues, the block arcade with its Minnie skirts and shopping Nuns. There is a subtlety in the imagery where nothing is overstated. An obvious angle one would photograph the hulk that is Flinders Street Station would be to stand adjacent to the station in front of St Paul’s Cathedral with a wide-angle lens to create an imposing, announcement of a city pining for recognition on a world stage, an image that could be printed on a postcard and posted across the world and to the mother country. Instead Angus sees beyond the obvious and looks for subtly in the everyday, taking his images as if like a voyeur in a city bustling with change and neon. You can feel his love for the city in each image; they are love letters to a city. “You have to know the city. I went to Sydney for a couple of weeks, my sister was living there, and I got keyed up but it wasn’t the same, I didn’t know the city, I knew of it, I had been there, but as a tourist, I didn’t really know the city like the Sydneysiders know it, what to really look for.”

So what was his process behind capturing these iconic images that only now are being rediscovered 40 years on? “It was what you called street photography or urban photography. It’s a city in life. I wanted to include people, I wanted to put adjuncts to them, you’ll see the edges, you’ll see houses or cars, they add to the picture. Because you are restricted by the camera, you had to think, how could I get an interesting picture without all of these lenses and filters?” It was this restriction of the fixed lens where we can truly see the talent and skill in Angus’ images. They are framed perfectly; his compositions of the everyday are what make his work so beautiful. “Composition is the secret of interesting photography” he explains. “Rarely did I take more than one picture of a scene; you were pretty frugal with your film as it was quite costly. I have noticed with digital you get wasteful, you start taking pictures and you’re just throwing them away like cards.”

It is one thing to be able to take a nice photo but in capturing those iconic moments in time there were some occupational hazards of walking the streets which was still suffering from a hangover of the great depression and post war suspicions. “I would walk the streets, looking for subjects. Some days you go all day and take very few pictures. You get abused as well. For instance if I was photographing an old fence in a lane, wouldn’t you think it was nothing? A lot of people would think ‘What’s wrong with this bloke?’ if you photographed a private home.” Angus would also take a conventional, professional approach to gaining access to buildings. “I used to write letters to firms for permission to photograph their buildings.” This would often turn out to be counterproductive, with the marketing departments offering Angus bland, corporate, staged photographs for him to feature in his proposed book of Melbourne.

From 1968 to 1971 Angus worked on producing a book that perhaps was ahead of its time. So did he find a publisher? Have we ever had the privilege of uncovering a dusty old Rigby published book on the city and people of Melbourne in second hand stores, filled with images that are so sincerely beautiful and intimate? The answer is surprising but not unexpected.

“One publisher said they we’re interested, we’ll have a look at it. I had it assembled with quite a voluminous draft narrative; they were very interested but had filled their publishing quotas. I tried two or three others but wasn’t getting anywhere. I remember one publisher, he showed me a book on Melbourne and said ‘sorry I already published this one, but yours would be far better.” Angus goes on to tell me: “I met a chap who was an ex representative of the Herald, I showed it to him and he was very interested but couldn’t get me a publisher. He also tried Angus & Robertson and a few others and I thought if he can’t do it I wouldn’t have much hope with it. So that ended the idea, I just put it away, went back into teaching until I retired in the early 90s”

After the death of his first wife in the 1990s, Angus moved to Queensland where he undertook a diploma course in Photography at Toowoomba Tafe in his mid seventies. Whilst studying he did various commercial jobs, wedding photography, photojournalism and selling images to photo libraries, but still treated it as a hobby. “I took up photography again when I retired; I went into a stock library and sold a few pictures, mainly for books and advertising. They just sent you a cheque for half the amount they got, only $50 a picture then, some were $100 depending on what magazine or book it was going into. I sold a few, I was happy doing it.”

So how have we come to rediscover or in fact newly discover this incredible image-maker? As life would have it, purely by chance, when two years ago Ben Albrecht, at the time joint-owner of Kozminsky Jewellery in Bourke Street Melbourne, was contacted to participate in a charity art auction as a guest auctioneer. In a back room he discovered a black and white photograph of a Japanese lady looking in a shop window in Collins Street and knew he had stumbled upon something special.

“I spoke to the lady who was in charge and asked ‘who took this photograph?’ I thought it was a one off. She told me it was Angus O’Callaghan. I asked for his telephone number as I would love to give him a buzz, which she replied ‘he’s in the other room, you can have a chat!’ It was a leap of faith because I knew by the image it was really special. I gave Angus my address to send me some images and five days later I got this post pack choc ‘o’ block full of transparencies. I started looking through them and thought these are phenomenal.”

No doubt these transparencies hadn’t been seen in public for decades and one wonders whether Angus himself had reviewed them since the disappointment of failing to secure a publisher all those years ago. So knowing he had stumbled on something incredible, Ben worked with Angus to scan and print editions of the collection through JCP Studios, which resulted in an exhibition of the collection two years ago, and a rediscovery of an important body of work that hadn’t been seen since 1971. A body of work, which Ben acknowledges, transcends generations.

“When we first had the exhibition there was the older generation of Australians, people who had lived through the 1960’s and the 70’s as 30 year olds, people who are my age and then you had the younger generation. The work really pleased a lot of different generations.”

In 1968 Angus began the undertaking of producing a book that failed to secure the funding of an open-minded publisher and now in 2012, Ben Albrecht is working on finally finishing the book that Angus set out to publish 40 years ago. And going by the auction results of his works this July, some prints well surpassing the thousand dollar mark, in particular ‘Royal Arcade’ (pictured) selling for $2,640, there has never been a better time than now for Angus to finally get the audience and appreciation he so duly deserves as one of this country’s greatest Photographers; an acknowledgement and appreciation that has eluded him throughout his life and career. Now in his 90th year, it has taken almost half a century for his work to be recognized which is something he is philosophical about. “Some things don’t happen, then other things do happen, it’s not always what you think is going to happen. I call life a winding track.”

Photographer Angus O’Callaghan will be discussing his photography that will be auctioned on May 2nd at 6:30pm.

The talk will be held on Wednesday the 1st of May at 6:30pm

Enquiries

Nicole Salvo

t: 03 8825 5624

e: Nicole Salvo